|

November 06, 2013

Alpaca Facts

Care, Behavior, Breeding, Fleece, and Shearing

By: Deb Blakey

Huacaya alpaca, our own Kenzie

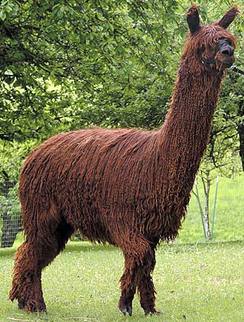

Example of suri alpaca, Fiorano

Our 3-sided barn for shelter

Breeding posture with inquisitive cria

Shearing is a big day!

DID YOU KNOW....?

Alpacas are members of the camel family, Camelidae. This family includes alpacas, llamas, guanacos, vicunas, and bactrian and dromedary camels. The vicuna is the wild ancestor of the alpaca.

The natural habitat of the alpaca is South America. Most of the approximately 3 million alpacas in the world today live in Chile, Peru, and Bolivia.

Alpacas have been domesticated for thousands of years as a fiber-producing animal. Their fiber contains no lanolin (the main cause of allergies to sheep wool), and is very fine, light weight, warm and comfortable. The fiber comes in 6 basic colors: white, beige, fawn, brown, gray, and black. Several of these colors have variations of shade (light fawn, medium fawn, dark fawn), making a wide array of 22 recognized colors – no other fiber animal has so many variations in color.

There are two types of alpaca: huacaya and suri. Huacaya alpacas are characterized by their crimpy fleece which stands out from their body, giving them a fuzzy, teddy bear look. The fleece of the suri alpaca hangs down in long, spiraled locks. There are far fewer suris than huacaya alpacas.

Most alpacas stand about 3 feet high at the shoulder, with variations of a few inches either way. Full-grown they weigh from 125 to 200 pounds.

Folks are often surprised to learn that alpacas have no upper incisors, but instead have a dental pad against which the lower incisors meet. They do have upper and lower molars for chewing.

They do not have a split hoof, but two toenails on a padded foot. Because of their light weight and their padded feet, they are easy on the terrain, unlike horses.

BASIC CARE

Alpacas are quite easy to care for. Like any domestic animal, they rely on the people tending them for food, water, shelter, protection from predators, and routine health care.

Feedwise, they cost just pennies a day to keep. A hundred pound bale of orchard grass hay (currently $9) will feed 6 full-grown alpacas for a week with two feedings a day. That’s about 11 cents a feeding for hay. If they are kept on pasture, only a small amount of acreage is needed – approximately one acre for six animals. It is recommended that their diets be supplemented with a good mineral mix formulated specifically for alpacas. During harsh weather, the end of pregnancy, or while nursing, extra nutrition can be given in the form of paca chow.

Shelter from rain, snow, wind, and the hot sun should be provided. A simple three-sided shed works very well. They don’t generally challenge fencing, although one of our naughty girls likes to push against a gate to see if it is latched and then sneak out if it isn’t! Six-foot high fencing and gates around the perimeter is recommended, not so much to keep the alpacas in, but to keep predators out.

Like us, they routinely need their toenails trimmed. Since their teeth continue to grow, occasionally their teeth need trimming by a vet. Vaccinations and worming should be given periodically.

BEHAVIOR

Alpacas are very inquisitive and curious, while at the same time rather shy and timid. Most are quite gentle. They don’t bite. Some do kick; it’s almost always because they are cornered and frightened. These can be worked with to "kick" this bad habit.

Alpacas have a reputation for spitting that isn’t usually merited. Like camels, alpacas can and do spit, but generally at each other and only when they are having a little "tiff." Some will spit at people when frightened or upset, but most do not. You will usually have fair warning if an animal is preparing to spit: it will stand its ground and raise its nose while laying its ears back. We have one animal that does this, but we rarely are spit at if we simply avoid direct eye contact with her. However, if you do catch some spit, it’s an experience you won't soon forget and one you will valiantly try to avoid in the future – green paca spit has an especially malodorous and lingering smell!

Generally on the quiet side, they make a variety of sounds, the most common called "humming," which can somewhat be humanly duplicated by saying, "Hmmmmmm???" If they get upset with each other (most commonly over food) they screech at each other. Very fearful alpacas may let out an ear-piercing scream. They also have a distinct alarm call to alert the herd to anything considered a possible threat. Then there is "orgling," a peculiar sound made by a male when it is breeding.

They can easily be halter trained. With further training they will put their nose in a halter, lift their feet on command, load in the trailer, and go through an obstacle course. Much more is possible, including pulling a tissue from the kleenex box and giving it to you when you sneeze!

We recommend these resources to learn more on training:

Marty McGee Bennett’s Camelidynamics at www.martymcgeebennett.com

John Mallon’s Gentling and Training Llamas and Alpacas at www.mallonmethod.com

Jim Logan’s Clicker Training at www.members.aol.com/Snowridge1

BREEDING

Alpacas are induced ovulators, meaning an egg is released because breeding has first taken place. Because of this, artificial insemination has not had good results to date. Baby alpacas are called "crias," males are called "machos," and females are "hembras." Females are generally ready to be bred by 18 months; males are of breeding age between 2 and 3 years. Gestation is quite long at 11 to 11 ½ months, sometimes over a year. Interestingly, most births occur during the day, generally needing little assistance from people, with the cria weighing 12 to 22 pounds. They very rarely have twins. Their lifespan is about 20 years.

FIBER and SHEARING

Alpacas need to be shorn once a year or they will get overheated during the hot summer months. They usually yield between 4 to 8 lbs. of fiber or more. Once shorn, most owners send a sample from the mid-side of the blanket (the prime fiber area on the animal) to a testing laboratory for a histogram. A histogram is a set of laboratory measurements which provides important basic information on the fineness of the fleece and other very valuable data for the breeder, including average fiber diameter (AFD), standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV), and percent of fibers greater than 30 microns. To understand more about such testing and an explanation of what the results indicate, go to the website of Yocom-McColl Testing Laboratories at www.ymccoll.com.

There are several characteristics of fiber to consider. Here are some definitions of terms:

Brightness: or luster, the sheen of the fiber; often more noticeable near the skin where the fiber is usually cleaner.

Crimp: the waviness in a lock of fiber giving it a corrugated look; crimp can be "bold" meaning the amplitude or height of each "wave" is very pronounced; crimp can have high "frequency" meaning there are many waves per inch along the length of the fiber. Crimp should be consistent along the entire length of the fiber.

Density: the number of hair follicles per square inch of skin; density is very desirable, especially in combination with fineness. If someone comments that an animal is dense, they are not knocking its intelligence, but giving a huge compliment!

Fineness: the diameter of the actual shaft of hair measured in microns; the lower the number, the finer the fleece. A "baby" fine fleece classification will measure between 20-22 microns; by comparison, human hair is 60-70 microns. Fineness less than 20 microns is also achievable and not uncommon.

Handle: the "feel" or softness and smoothness of the fiber; although this is subjective, those who have sorted through many fleeces by hand are able to accurately judge between a fine fleece and one that is less fine by its handle.

Medullation: guard hair fibers with no crimp that usually grow longer and are much coarser and stiffer than the rest of the blanket. These guard hairs are usually found on the chest and belly; the less medullation, the better.

Staple Length: the length the animal’s fiber grows between shearings, usually 3 to 6 inches per year.

Uniformity: consistency throughout the fleece of each of the valuable attributes of fiber listed above, with little deviation in any one characteristic.

|